[Versión en español] [Version en français] [Deutsche Fassung]

Introduction

Despite the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the deployment of Russian troops along the Ukrainian border in 2021, no one believed that Russia would invade Ukraine even if the evidence suggested otherwise. However, considering Russian propaganda about Ukraine might have been useful in assessing the likelihood of a full-scale invasion. Therefore, understanding how Russia views Ukraine has proven crucial to understanding the current security situation in Eastern Europe, a goal to which this paper aims to contribute.

The Kremlin's view of Ukraine as part of the Russian world did not change after the collapse of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR or Soviet Union), so Russia will not tolerate the slightest rapprochement of Ukraine to the West, be it the European Union (EU) or the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Following this reasoning, it is logical that Russia felt the need to intervene in Ukraine's internal affairs after the Maidan Revolution resulted in the ouster of pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych because he had refused to sign an association agreement with the EU. Fearing loss of influence over Ukraine, Russia retaliated by invading the Crimean peninsula and supporting separatists in the Donbas region.

A similar scenario took place in 2022 when Russia felt that Ukraine was getting too close to NATO, even if its accession to the organization was highly unlikely, and demanded to veto Ukraine's future NATO membership, as well as the withdrawal of troops from Poland and the Baltic states. Following NATO's refusal to accede to its demands, which some analysts have called a diversionary maneuver, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

These actions cannot be understood without considering how Russian propaganda portrays Ukraine to garner support for its foreign policy objectives, which is precisely the focus of this paper.

The methodology is based on a literature review of existing studies on the subject, including books, journal articles, newspaper articles and conference papers, which serve as a starting point for the analysis.

Before delving into the topic at hand, it is necessary to define the main concepts around which the article revolves: propaganda and disinformation. Harold D. Lasswell described the former as "the manipulation of symbols for the purpose of influencing attitudes on controversial issues," [1] while "disinformation" is used to refer to "intentionally false, incomplete or misleading information (often combined with true information), which seeks to deceive and/or confuse the target." [2] In this case, Russia is spreading disinformation about Ukraine and the Ukrainian people through various media to convince its audience that Ukraine belongs to it.

Historical background

Modern Russian propaganda and disinformation techniques are largely based on those used by the Soviet Union during the Cold War, although the scope, targets and means have changed. Propaganda is not a Soviet invention at all and was first implemented on a large scale during the First World War. World War II consolidated its use as a weapon of war, but it was not until the Cold War that it came to the fore. The Soviet government began sponsoring the film industry for this purpose shortly after the October Revolution of 1917, following Vladimir Lenin's emphasis on "techniques of informal penetration, propaganda, agitation and political deception as integral elements of the strategy of the Communist Party." [3]

The techniques used during this era, known as active measures, were aimed at expanding Soviet power and spreading communism throughout the world. [4] Although the USSR did not distinguish between overt and covert actions or propaganda and action, active measures can be classified into two categories: propagandistic falsification and misinformation or disinformation. The former includes mostly overt actions initiated by the Committee for State Security (KGB), such as the creation of front organizations, falsification of official publications and publication of falsified evidence, while the latter type of operations were coordinated through the International Information Bureau of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to mislead and disinform the target, either overtly or covertly. [5]

The success of Soviet propaganda was based on the ability of the Bolsheviks to get people to take their worldview for granted, which they achieved by imposing strict censorship and eliminating opponents who might offer a different perspective. [6] Three key concepts describe the Soviet and Russian approach to conflict: active measures, which have already been explained, organizational weapons, and reflexive control.

An organizational weapon can be described as "the creative energy of the masses organized and directed by the authorities to achieve a specific goal" [7] and is closely related to the concept of political maneuver, which is "the ability [of the party leadership] to direct the mass movement in the right way, depending on the objective situation." [8] Reflexive control, i.e., "a process by which one enemy conveys the reasons or basis for making decisions to another" provides the practical means to achieve the disorganization and disorientation of the enemy, indicating that the deployment of an organizational weapon has been successful. [9] Thus, the process is as follows: active measures in the form of forgeries, agents of influence, etc. are deployed as organizational weapons to gain reflexive control so that "a carefully constructed false message [...] is secretly introduced into the opponent's communication system. to deceive his [sic] decision making elite or public opinion." [10]

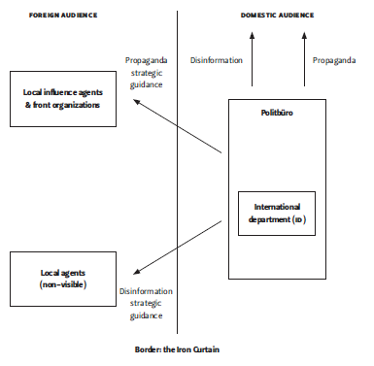

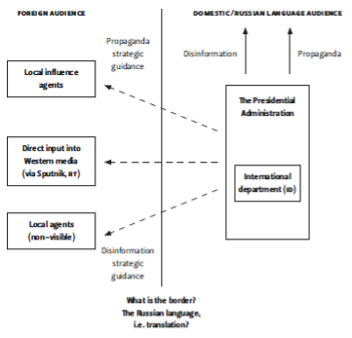

Soviet propaganda was characterized by its continuity, flexibility and adaptability, as it was designed to operate over an extended period of time and could adapt quickly to changing circumstances. [11] Contemporary Russian propaganda is based on Soviet techniques, but has also incorporated modern technologies for its dissemination, such as the Internet and social networks. It is also fast and continuous, but does not place importance on truth or consistency, relying as it does on fabricated evidence and changing versions of events. [12] Figures 2 and 3 depict the distribution of Soviet and Russian propaganda channels. The only major change is the intrusion into the Western media, to which the Soviet Union had no access, through national news agencies such as RT and Sputnik. These actors are discussed in more detail later in this paper.

Soviet propaganda served as the very foundation for Russian propaganda not only with respect to its methods but also to the narratives it constructed. Even before the Russian Revolution, which overthrew the imperial government and established a socialist one, Russians believed that the lands to the west rightfully belonged to the Russian sphere of influence as Russia's "borderlands." [15] This narrative, specifically in relation to Ukraine, would later become the cornerstone of Russian propaganda. During the Soviet period, Moscow, Leningrad and Novosibirsk became the centers of intellectual life, while other major cities such as Kiev were considered "provincial backwater of Soviet Russian culture." [16] In addition, Russians were characterized as the big brothers of all other peoples under Soviet rule, another key narrative that continues to the present. Thus, Ukraine came to be known as "Little Russia" (Малоророссия), an integral part of the Russian world, and Ukrainians were simply children in disguise. [17] This is one of the justifications Russia has used to justify its repeated violations of Ukrainian sovereignty.

Narratives

As mentioned in the previous section, Russian propaganda relies heavily on Soviet methods and narratives, but has incorporated other narratives that better fit the current scenario to remain relevant and convey its message. The most common strategy Russia has employed is to tell people "stories about history" [18] which it adapts as necessary for its strategic goals. For example, after the illegal annexation of Crimea, the Kremlin first denied its involvement and then justified the intervention by claiming that Crimea had always belonged to Russia.

The following are the five most common narratives about Ukraine, in approximate order of appearance.

"Ukraine is Russia's failed shadow."

Based on the belief that Russians and Ukrainians are the same people, one of the most widespread narratives is based on the myth of the Russian nation, according to which Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine are part of the Russian world and not independent states. One information agency even went so far as to suggest that "until 1936, there was no such thing as "Kazakhstan" or "Kazakh"" and that "also "Ukrainians" are an invention." [19]

In the case of Ukraine, Russia bases this claim on the controversy surrounding the etymology of the country's name, which is generally considered to derive from the Old East Slavic ѹкраина (oukraina) and means "borderland" in reference to Russia. [20] Some scholars argue that there is a difference between україна (oukraina, "territory") and окраїна (okraina, "borderland"), since "krai" means "segment, piece; piece of land", ou - means "in", and o- means "around", so the distinction would be between the meanings "in the territory" and "around the territory". [21] According to the latter interpretation, which prevails in Russian media, "Ukraine" refers to the border areas or the outskirts of Russia and, therefore, cannot be the name of an independent state.

Based on the concept of the unity of the Russian world, Russia claims that Russians and Ukrainians, as well as Belarusians and Kazakhs, are the same people; however, it has referred to Ukraine as a "friendly and brotherly state of Russia." [22] Demonstrating its usual inconsistency, Russian propaganda contradicts itself by claiming that Ukrainians are both "little Russians" and "friendly brothers". As Hrytsak et al. (2019) reasons, "only two different nations can be "sisters" to each other." [23]

The second layer of this narrative describes Ukraine as "a failed state that has been unable to provide order and welfare to its population" due to corruption and incompetence. [24]

"Ukraine is an artificial project of the West."

This second narrative also relies on the myth of Russians and Ukrainians as one people. In this case it claims that Ukraine cannot be an independent state because it was invented by foreigners, mainly Austrians and Poles, to divide the Russian people. According to this narrative, Ukraine was created by the Austro-Hungarian Empire to play the Russians against each other and its name is an invention of a Polish author and refers to the outskirts or border areas of Poland. [25]

A second related justification suggests that the West wants to divide Russians and eliminate the "great Russian people" by claiming that Ukrainians are not Russians. [26] For example, Russian media insist that the conflict in Ukraine is actually a U.S.-driven civil war to divide Slavic Christians. [27] Similarly, Russian propaganda alleges that the West had promised Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that it would not expand NATO and is therefore violating this promise by forcibly expanding and deploying troops near Russia's borders. [28]

In fact, NATO never formally made such a promise and has not forced Eastern European countries to join the organization; it is the latter that have shown interest in becoming members. The invasion of Ukraine has produced precisely the opposite effect desired by the Kremlin: two more countries-Finland and Sweden-one of which borders Russia-have formally applied for NATO membership. In addition, following the invasion, countries of the former USSR such as Georgia and Moldova, as well as Ukraine, have applied to become EU member states.

By framing the conflict in Ukraine as a battle between the West and Russia using Cold War rhetoric, Russian propaganda further undermines the Ukrainian state and strips Ukraine of its free will.

"Crimea, Donbas and southeastern Ukraine belong to Russia."

Following the overthrow of Yanukovych during the Maidan revolution in 2014 and his replacement by pro-European President Petro Poroshenko, Russia annexed Crimea and began providing support to pro-Russian separatists in the Donbas. During this time Russian propaganda put forward the idea of Novorossiya (New Russia) to give an identity to the separatist regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. [29] Novorossiya was presented as a historical region in southeastern Ukraine based on the homonymous region that was part of the Russian Empire after the latter conquered the Crimean Khanate. [30]

Even though the concept of Novorossiya never achieved great popularity, the discussion around the identity of Crimea came to the forefront and became a bone of contention, as evidenced by the official speech of Russian President Vladimir Putin after the annexation of the peninsula: "in the hearts and minds of people, Crimea has always been an inseparable part of Russia." [31] In addition to its geostrategic relevance due to its location on the Black Sea, Crimea also has a special significance for Russia, as it is considered the birthplace of Eastern Slavic Orthodox Christianity because Prince Vladimir of Kievan Rus was baptized there [32].

Moreover, Russian propaganda claims that the transfer of the peninsula to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1954 was procedurally incorrect and even illegal because it was not ratified by a referendum. [33] That is why Russia believes that the 2014 Crimean referendum restored the historical justice of which its inhabitants had been deprived.

"Ukrainian nationalists are fascists and Russophobes."

Russian propaganda has always portrayed the USSR as the savior of Europe during World War II for liberating the continent from the Nazis. The war is known in Russia as the Great Patriotic War and is therefore "the most sacred achievement" in the country's history. [34] "As a consequence, labeling someone a "fascist" is a powerful way of appealing to the values of Russians, who associate World War II with fascist horrors and crimes."[35] It is no wonder then that this label is used for Ukrainians trying to leave Russia's sphere of influence.

One of the alleged reasons why Ukrainian nationalists, or simply pro-European Ukrainians, are neo-Nazis is that the national salute Слава Україні! (Glory to Ukraine!) was also the motto of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, a paramilitary group that fought for the country's independence from the Soviet Union. Russian propaganda claims it is a translation of the Nazi greeting Sieg Heil! (Glory to Victory!), but in fact it was coined before World War II and the rise of Nazism.

The fascist label began to be used to refer to the Ukrainian government and military, in which there are neo-Nazi groups, after the 2014 presidential election, but gained prominence during the Euromaidan that preceded the Maidan Revolution as an umbrella term for Ukrainian nationalists. [36] This is how the fall of Yanukovych was characterized as a neo-Nazi coup that overthrew a democratically elected president with the support of the West, [37] even though far-right groups had a limited presence in the uprising and performed poorly in the 2019 elections. [38]

The annexation of Crimea was described as a "peaceful demonstration of normal people who wanted to protect themselves from the "fascists in Kiev"" in which Russia had intervened to act as a negotiator. [39] This is false for several reasons, but the main one is that any manifestation of Nazism (and communism) in Ukraine is forbidden by law. [40]

The characterization of Ukrainian troops as neo-Nazis intensified after the invasion of Ukraine and the main Russian TV channel reported that a village had been liberated from "neo-Nazis." [41] This tactic has been dubbed "schizofascism" and refers to "real fascists calling their enemies 'fascists'" using a Nazi technique of telling a lie so big "that the psychic cost of resisting it is too high," such as that "an autocrat wages a genocidal war against a democratic nation with a Jewish president and calls the victims Nazis." [42]

A second defamatory layer was subsequently added to portray the Ukrainian government as Russophobic following the introduction of a law diminishing the official status of the Russian language in favor of Ukrainian but not banning it, as Russia claimed. [43] According to the Kremlin, this Russophobia is being fueled by the West and has led to discrimination against ethnic Russians.

"Ukraine is carrying out genocide against the Russian-speaking population."

This narrative is the most recent and the main justification for the invasion of Ukraine, which Putin intends to "denazify." It claims that the Russophobic Ukrainian government is carrying out genocide against the Russian-speaking population of the Donbas, where clashes between the Ukrainian army and Russian-backed separatists have been taking place since 2014.

This is how Russian propaganda conjures up the specter of World War II and Nazi genocide and presents Russia as the savior once again, only this time the West is not an ally but the enemy. The mainstream Russian media have echoed this narrative and frame the invasion as "a struggle of ethnic Russians against fascism." [44] Russia used a similar strategy during the 2008 Russo-Georgian war when Russian troops invaded Georgia to support South Ossetian separatists.

A parallel narrative portrays the situation in eastern Ukraine since 2014 as a humanitarian catastrophe. Official Russian statements emphasized "the plight of civilians in the region, the cooperative and transparent nature of Russia's intentions and that aid would be delivered to civilians," [45] again creating a dichotomy between good and evil and portraying Russia as the protector of defenseless civilians who are being targeted because they speak Russian and not Ukrainian.

Actors

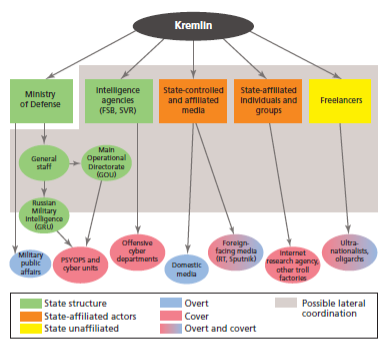

After analyzing Russia's narratives on Ukraine, this section is devoted to the actors who have helped to spread them. It is no secret that the government is the main driver of Russian propaganda, as in any other type of propaganda, but it is less clear to what extent other actors are involved. Figure 4 shows a proposal of how the propaganda machine is organized.

The organization of this section is roughly based on Figure 4 according to which the first subsection corresponds to the state structure; the second deals with the media, which are controlled by or affiliated with the state; the third subsection refers to civil society, both individuals and groups, regardless of their affiliation; and the fourth is devoted exclusively to the Russian Orthodox Church, which is difficult to categorize.

The State

As with narratives, state involvement in propaganda began during the Soviet era. The Kremlin used Radio Moscow and press agencies such as TASS and RIA Novosti to paint an optimistic picture of life in the Soviet Union through reports of successful collective farms and national heroes who had gone into space. [47] This overt propaganda was aimed at people who were already living under a communist regime and therefore did not need to be convinced.

Covert propaganda, on the other hand, was disseminated by front organizations with innocent names such as "World Peace Council" or "Vietnam Medical Committee," [48] since the Soviet government did not have access to the Western media, unlike today.

After the fall of communism, Russia began to develop its soft power to remain a relevant player internationally based on "the presence of Russian minorities [in neighboring countries], the Russian language, post-Soviet nostalgia and the strength of the Russian Orthodox Church." [49] During this period the Kremlin redoubled its efforts and hired Western public relations agencies to carry out its propaganda offensive.

Today state propaganda comes directly from the Kremlin in the form of official statements that sometimes contradict each other. For example, during the invasion of Crimea, which was presented as an internal conflict, Putin denied the presence of Russian troops on Ukrainian territory, but later admitted that Russian soldiers had crossed the Ukrainian border. The full-scale invasion in 2022 was described as a special military operation aimed at protecting Russians living in the Donbas, but after announcing the partial mobilization of reservists, Putin claimed that the goal was to safeguard Russia's territorial integrity. These two examples show that the Russian government is not afraid to contradict itself.

Media and communication

Although the approach to the media has changed since the Soviet era, the goal is the same: to control the media and, therefore, the narrative. Tactics have shifted from "direct pressure and intimidation of journalists to a policy of redistributing media assets to business groups that support the government's agenda." [50] The result is that the largest media outlets, including news agencies, newspapers, radio stations, and television channels, are either directly controlled by the state (Piervy Kanal, RIA Novosti, RT, Rossiya 1, Sputnik, TASS) or managed by state corporations (NTV) or private companies linked to the government (REN-TV). [51]

Some of them have multiple language versions and are broadcast worldwide, such as Piervy Kanal, RT and Sputnik; the latter two have been banned in the European Union and the United Kingdom since the invasion of Ukraine for broadcasting pro-Russian propaganda. RT was created specifically to compete with global media such as Al Jazeera, BBC World and CNN and to defend Russian interests. [52] During the Russo-Georgian war, RT's editor-in-chief openly admitted that the media outlet was waging an information war to support Russia's foreign policy. It has also been proven that RT has been successful in affecting the political opinion of the television audience to serve Russian interests, including in the United States. [53]

Civil society

Just before the Crimean annexation, Russian propaganda began to take over the Internet thanks to the Internet Research Agency, an online propaganda company allegedly funded by a close friend of Putin's that was created to support Russian actions in Ukraine. The organization has come to be known as a "troll factory" that produces content "to distort, distract from, dismiss and deny Russia's involvement in the [Ukrainian] conflict" [54] by linking fake media websites that look like real ones in tweets that also include hashtags and mentions to increase visibility.

The so-called trolls, who allegedly work around the clock and post 135 comments a day, [55] have been instructed never to write anything negative "about the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic or the Luhansk People's Republic and never anything good about the Ukrainian government." [56] They also organized to post on the websites of Western newspapers such as The Guardian in support of Russia's annexation of Crimea.

Thanks to them, disinformation and propaganda have also spread at the grassroots level, which "indicates an inherent understanding of how to penetrate societies naturally skeptical towards mainstream information channels," [57] as is the case in the post-Soviet environment due to the widespread dissemination of government propaganda during the Soviet era.

Important civil society actors, such as think tanks and academics, are also increasingly controlled by the Russian government so that "their conclusions and instructions align more closely with the Kremlin's goals and narratives." [58] This has led to a brain drain, as many experts have left the country intimidated by the government, thus creating a vicious circle in which internal dialogue suffers: academia and think tanks reinforce government policies and the government influences the conclusions of the former.

Russian Orthodox Church

Putin has repeatedly praised the Russian Orthodox Church since the beginning of his first presidential term and has taken pains to present himself as a religious man who upholds traditional values. This relationship is reciprocal, as Patriarch Cyril of Moscow said that Russian defense capabilities should be reinforced with Orthodox values, thus merging security and religion in what has been called "spiritual security." [59]

The Russian Orthodox Church's attitude provoked tensions with the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in 2009, when Patriarch Cyril endorsed the Kremlin's view of Ukraine as part of the Russian world, as well as the concept of Novorossiya, and defended "Russia's historical and religious ties with Kiev and Crimea." [60]

More recently, the Patriarch Cyril expressed his support for the invasion of Ukraine, going so far as to call it a holy war, thus reinforcing the status of the Russian Orthodox Church as an ideological ally of the Russian government, which in turn uses the Church's values to justify its actions. It exerts such great influence over the Kremlin that Putin obeyed its call for a cease-fire on the front during Orthodox Christmas and ordered a 36-hour truce. [61]

Characteristics and tactics

As explained in section two, contemporary Russian propaganda is largely based on Soviet techniques, but it also has some distinctive features such as "a large number of channels and messages and an unabashed willingness to spread partial truths or pure fictions." [62] This section expands on the means and tactics used by different actors to convey the narratives discussed in section three.

Due to the aforementioned characteristics, Russian propaganda is continuous and repetitive and is not committed to consistency, as has been demonstrated in different examples throughout this paper. Its effectiveness can be attributed to these characteristics, as it has been shown that "multiple sources are more persuasive than a single source," "endorsement by a large number of users increases the receiver's trust in the information," "repeated exposure to a statement has been shown to increase its acceptance as true." [63] While the arguments in favor of multichannel, continuous, repetitive propaganda make intuitive sense, its success despite a lack of commitment to consistency or truth is more puzzling.

Although it often invents evidence and sources, Russian propaganda enjoys credibility due to several factors. First, people often do not know how to distinguish between true and false information, and the refutation of a false argument reaches a smaller audience than the original message. Second, content that arouses negative emotions, which is often the case with Russian disinformation, is more persuasive and therefore more likely to be transmitted.

Third, confirmation bias, i.e., being exposed to opinions that confirm existing beliefs, plays an important role in the social network environment. Finally, "false statements are more likely to be accepted if they are supported by evidence, even if that evidence is false," [64] and because people do not normally expect the information they receive to be false, they are unlikely to investigate to refute the arguments.

Russian disinformation is arguably more successful online, particularly outside the country, due to its characteristics and the reasons mentioned above. Narratives such as the one portraying Ukrainian nationalists and the government as fascist can become weapons to produce strong negative feelings such as anger and fear, which can lead to hatred and ultimately violence. [65]

This strategy is implemented on multiple platforms, including not only major social networks such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube, but also others such as Reddit and Tumblr and Odnoklassniki (OK) and Vkontakte (VK) in Russian, as well as messaging apps such as Telegram and WhatsApp and blogging platforms. Moreover, some of them are targeted to specific communities: Tumblr, for example, was used to target African-American audiences, [66] while OK and VK are aimed at Russian speakers.

To spread propaganda, civil society actors, such as IRA trolls, use photographs of real people to create fake profiles or even impersonate them. [67] They privilege quantity over quality by "favoring volume over plausibility or consistency" through the use of bots and the promotion of existing content from extremist sources, such as neo-Nazi websites and far-right political parties. [68]

While bots do not target specific users and only aim to maximize the number of people who see a message by retweeting rather than producing content, human actors use data mining techniques to gather information about social network users and specific audiences using Facebook's advertising algorithms. [69] This creates bubbles in social networks in which users' beliefs and opinions reverberate due to confirmation bias.

The Internet has thus contributed to creating a two-way propaganda model in which official propaganda "interacts with target audiences who play an active role in the production of meaning." [70] This is another reason why Russian propaganda is so effective, as not only state-affiliated actors produce disinformation, but also individuals disseminate it and even produce their own content.

Conclusions

Russia has used disinformation campaigns since even before the Cold War to turn public opinion in its favor and justify its foreign policy actions, from the annexation of Crimea to the invasion of Ukraine. Through a series of narratives tailored to the context it has challenged Ukraine's sovereignty and independence with the ultimate goal of incorporating it back under its rule.

Different actors under the Kremlin's control or influence, including the media, civil society and the Russian Orthodox Church, have used a wide range of channels to spread disinformation, from television programs to social media posts, both inside and outside Russia. They have been successful despite their lack of commitment to consistency because Russian propaganda is characterized by the continuous and repetitive manner in which it is disseminated. In addition, having the public produce their own content has also helped to further spread the narratives.

To sum up, by portraying Ukraine as part of the Russian world and Ukrainians as Russians and claiming that its government is Russophobic and fascist, Russia is trying to legitimize the invasion as an operation to denazify the country and protect the ethnic Russian population from genocide because it fears losing influence over former Soviet territories to the West. The use of rhetoric evoking World War II, which Russians refer to as the Great Patriotic War, is intended to arouse nostalgic feelings to compensate for Russia's growing impotence on the international stage.

Bibliography

Aron, Leon. “Russian Propaganda: Ways and Means.” American Enterprise Institute, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep03227.

Bittman, Ladislav. “The Language of Soviet Disinformation” in Contemporary Soviet Propaganda and Disinformation: A Conference Report. United States Department of State, 1987.

Bittman, Ladislav. The KGB and Soviet Disinformation: An Insider’s View. McLean, VA: Pergamon Brassey’s, 1985.

Boyd-Barrett, Oliver. “Ukraine, Mainstream Media, and Conflict Propaganda.” Journalism Studies 18, no. 8 (2015): 1016–1034. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2015.1099461.

Boyte, KJ. “An Analysis of the Social-Media Technology, Tactics, and Narratives Used to Control Perception in the Propaganda War Over Ukraine.” Journal of Information Warfare 16, no. 1 (2017): 88–111. ISSN 1445-3347.

Charron, Austin. “Whose is Crimea? Contested Sovereignty and Regional Identity.” Region 5, no. 2 (2016): 225–256. https://doi.org/10.1353/reg.2016.0017.

Cottiero, Christina, Katherine Kucharski, Evgenia Olimpieva, and Robert W. Orttung. “War of words: The impact of Russian state television on the Russian Internet.” Nationalities Papers: The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity 43, no. 4 (2015): 533–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2015.1013527.

Doroshenko, Larissa and Josephine Lukito, “Trollfare: Russia’s Disinformation Campaign During Military Conflict in Ukraine.” International Journal of Communication 15 (2021): 4662–4689. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/16895/3587.

EUvsDisinfo. “Disinfo: For the West, it is necessary to divide the Russians.” 29 de enero de 2016. https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/for-the-west-it-is-necessary-to-divide-the-russians.

EUvsDisinfo. “Disinfo: We have Nazis in Ukraine, not in Russia.” 9 de julio de 2019. https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/nazis-rule-ukraine.

EUvsDisinfo. “Disinfo: Ukraine is a Russophobic, Nazi state, controlled by the US.” 30 de marzo de 2020. https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/ukraine-is-a-russophobic-state-with-nazis-controlled-by-the-us.

EUvsDisinfo. “Disinfo: Myth about Ukraine as a separate nation was created in the USSR.” 16 de abril de 2020. https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/myth-about-ukraine-and-ukrainians-as-a-separate-nation-was-created-in-the-ussr/.

EUvsDisinfo. “Disinfo: Ukrainians and Kazakhs did not exist as ethnic groups before the USSR.” 13 de agosto de 2021. https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/ukrainians-and-kazakhs-did-not-exist-as-ethnic-groups-before-the-ussr.

EUvsDisinfo. “Disinfo: The current event in Ukraine is a civil war provoked by the US: Russians and Ukrainians are one people.” 28 de febrero de 2022. https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/the-current-event-in-ukraine-is-a-civil-war-provoked-by-the-us-russians-and-ukrainians-are-one-people.

Geissler, Dominique, Dominik Bär, Nicolas Pröllochs, and Stefan Feuerriegel. “Russian propaganda on social media during the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.” 2022. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2211.04154.

Gessen, Masha. “Inside Putin’s propaganda machine.” The New Yorker. May 18, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-communications/inside-putins-propaganda-machine.

Grigor (Khaldarova), Irina and Mervi Pantti. “Visual images as affective anchors: strategic narratives in Russia’s Channel One coverage of the Syrian and Ukrainian conflicts.” Russian Journal of Communication, 13, no. 2 (2021): 140–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/19409419.2021.1884339.

Hrytsak, Yaroslav, Kyrylo Halushko, Yana Prymachenko, Hennadii Yefimenko, Serhii Hromenko, Ivan Homeniuk, Volodymyr Yermolenko, Oksana Iliuk, Olena Sorotsynska, and Artur Kadelnyk. Re-Vision of History: Russian Historical Propaganda and Ukraine. Kyiv: K.I.S., 2019.

Jaitner, Margarita and Peter A. Mattsson. “Russian Information Warfare of 2014.” In 7th International Conference on Cyber Conflict: Architectures in Cyberspace. M. Maybaum, A.-M. Osula, and L. Lindström (eds.). Tallinn: NATO CCD COE Publications, 2015.

Jones, James. “Inside Ukraine’s Propaganda War.” Frontline, 14 de marzo de 2014. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/inside-ukraines-propaganda-war/.

Khaldarova, Irina and Mervi Pantti. “FAKE NEWS: The narrative battle over the Ukrainian conflict.” (2016): 891–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2016.1163237.

Mejis, Ulises A and Nikolai E Vokuev. “Disinformation and the media: the case of Russia and Ukraine.” Media, Culture & Society 39, no. 7 (2017): 1027–1042, https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716686672.

Mulford, Joshua P. “Non-State Actors in the Russo-Ukrainian War.” Connections QJ 15, no. 2 (2016): 89–107. https://doi.org/10.11610/Connections.15.2.07.

Online Etymology Dictionary. “Ukraine.” 20 de junio de 2022. https://www.etymonline.com/word/Ukraine#etymonline_v_4435.

Paul, Christopher and Miriam Matthews. “The Russian ‘Firehose of Falsehood’ Propaganda Model: Why It Might Work and Options to Counter It.” RAND Corporation, 2016.

Pivtorak, Hryhoriy. “«Україна» — це не «окраїна».” 2001. Ізборник. http://litopys.org.ua/pivtorak/pivt12.htm.

Putin, Vladimir. “Address by President of the Russian Federation.” President of Russia. 18 de marzo de 2014. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20603.

Pynnöniemi, Katri, and András Rácz (eds.). Fog of Falsehood: Russian Strategy of Deception and the Conflict in Ukraine. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of International Affairs, 2016. https://www.fiia.fi/en/publication/fog-of-falsehood.

Riekstins, Maris. “Putin’s Propaganda.” Foreign Affairs. Noviembre/enero de 2014. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2014-12-24/putins-propaganda.

Saikali, Elie. “Patriarch Kirill: The politically influential head of the Russian Orthodox Church.” France 24. 9 de enero de 2023. https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20230109-patriarch-kirill-the-politically-influential-head-of-the-russian-orthodox-church.

Treyger, Elina, Joe Cheravitch, and Raphael S. Cohen. Russian Disinformation Efforts on Social Media. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2022.

Van Herpen, Marcel H. Putin’s Propaganda Machine. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

Von Hagen, Mark. “Does Ukraine Have a History?.” Slavic Review 54, no. 3 (1995): 658–673. https://doi.org/10.2307/2501741.

Yuhas, Alan. “Russian propaganda over Crimea and the Ukraine: how does it work?.” The Guardian. 17 de marzo de 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/17/crimea-crisis-russia-propaganda-media.

Footnotes

[1] Katri Pynnöniemi and András Rácz (eds.), Fog of Falsehood: Russian Strategy of Deception and the Conflict in Ukraine (Helsinki: Finnish Institute of International Affairs, 2016), https://www.fiia.fi/en/publication/fog-of-falsehood, 27.

[2] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 29.

[3] Ladislav Bittman, The KGB and Soviet Disinformation: An Insider’s View (McLean, VA: Pergamon Brassey’s, 1985), 35.

[4] Bitman, Soviet Disinformation.

[5] Bitman, Soviet Disinformation.

[6] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 32.

[7] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 35.

[8] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 35.

[9] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 36.

[10] Ladislav Bittman, “The Language of Soviet Disinformation,” in Contemporary Soviet Propaganda and Disinformation: A Conference Report (United States Department of State, 1987), 113.

[11] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 38.

[12] Christopher Paul and Miriam Matthews, “The Russian ‘Firehose of Falsehood’ Propaganda Model: Why It Might Work and Options to Counter It” (RAND Corporation, 2016).

[13] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 41.

[14] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 47.

[15] Mark von Hagen, “Does Ukraine Have a History?,” Slavic Review 54, no. 3 (1995): 658–673. https://doi.org/10.2307/2501741.

[16] Von Hagen, “Does Ukraine Have a History?,” 663.

[17] “Disinfo: Myth about Ukraine as a separate nation was created in the USSR,” EUvsDisinfo, 16 de abril de 2020, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/myth-about-ukraine-and-ukrainians-as-a-separate-nation-was-created-in-the-ussr/.

[18] Yaroslav Hrytsak et al., Re-Vision of History: Russian Historical Propaganda and Ukraine (Kyiv: K.I.S., 2019), 4.

[19] “Disinfo: Ukrainians and Kazakhs did not exist as ethnic groups before the USSR,” EUvsDisinfo, 13 de agosto de 2021, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/ukrainians-and-kazakhs-did-not-exist-as-ethnic-groups-before-the-ussr.

[20] “Ukraine”, Online Etymology Dictionary, 20 de junio 2022, https://www.etymonline.com/word/Ukraine#etymonline_v_4435.

[21] Hryhoriy Pivtorak, “«Україна» — це не «окраїна»,” 2001, Ізборник, http://litopys.org.ua/pivtorak/pivt12.htm.

[22] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 91.

[23] Hrytsak et al., Re-Vision of History, 11.

[24] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 92.

[25] Hrytsak et al., Re-Vision of History, 13.

[26] “Disinfo: For the West, it is necessary to divide the Russians,” EUvsDisinfo, 29 de enero de 2016, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/for-the-west-it-is-necessary-to-divide-the-russians.

[27] “Disinfo: The current event in Ukraine is a civil war provoked by the US: Russians and Ukrainians are one people,” EUvsDisinfo, 28 de febrero de 2022, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/the-current-event-in-ukraine-is-a-civil-war-provoked-by-the-us-russians-and-ukrainians-are-one-people.

[28] Maris Riekstins, “Putin’s Propaganda,” Foreign Affairs, noviembre/diciembre de 2014, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2014-12-24/putins-propaganda.

[29] Elina Treyger, Joe Cheravitch, and Raphael S. Cohen, Russian Disinformation Efforts on Social Media (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2022), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4373z2.html, 111.

[30] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 106.

[31] Vladimir Putin, “Address by President of the Russian Federation,” President of Russia, 18 de marzo de 2014, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20603.

[32] Austin Charron, “Whose is Crimea? Contested Sovereignty and Regional Identity,” Region 5, no. 2 (2016): 225–256, https://doi.org/10.1353/reg.2016.0017, 232.

[33] Hrytsak et al., Re-Vision of History, 18.

[34] Irina Khaldarova and Mervi Pantti, “FAKE NEWS: The narrative battle over the Ukrainian conflict,” (2016): 891–901, https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2016.1163237, 895.

[35] Christina Cottiero et al., “War of words: The impact of Russian state television on the Russian Internet,” Nationalities Papers: The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity 43, no. 4 (2015): 533–555, https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2015.1013527.

[36] Khaldarova and Pantti, “FAKE NEWS,” 895.

[37] Oliver Boyd-Barrett, “Ukraine, Mainstream Media, and Conflict Propaganda,” Journalism Studies 18, no. 8 (2015): 1016–1034, https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2015.1099461, 1025.

[38] “Disinfo: Ukraine is a Russophobic, Nazi state, controlled by the US,” EUvsDisinfo, 30 de marzo de 2020, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/ukraine-is-a-russophobic-state-with-nazis-controlled-by-the-us.

[39] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 203.

[40] “Disinfo: We have Nazis in Ukraine, not in Russia,” EUvsDisinfo, 9 de julio de 2019, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/nazis-rule-ukraine.

[41] Masha Gessen, “Inside Putin’s propaganda machine,” The New Yorker, 18 de mayo de 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-communications/inside-putins-propaganda-machine.

[42] Masha Gessen, “Inside Putin’s propaganda machine”.

[43] Alan Yuhas, “Russian propaganda over Crimea and the Ukraine: how does it work?,” The Guardian, 17 de marzo de 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/17/crimea-crisis-russia-propaganda-media.

[44] Irina Grigor (Khaldarova) and Mervi Pantti, “Visual images as affective anchors: strategic narratives in Russia’s Channel One coverage of the Syrian and Ukrainian conflicts,” Russian Journal of Communication, 13, no. 2 (2021): 140–162, https://doi.org/10.1080/19409419.2021.1884339, 147.

[45] Pynnöniemi and Rácz, Fog of Falsehood, 76.

[46] Treyger, Cheravitch, and Cohen, Russian Disinformation Efforts, 34.

[47] Marcel H. van Herpen, Putin’s Propaganda Machine (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), 106.

[48] Van Herpen, Putin’s Propaganda Machine, 106.

[49] Van Herpen, Putin’s Propaganda Machine, 109.

[50] Ulises A. Mejis and Nikolai E. Vokuev, “Disinformation and the media: the case of Russia and Ukraine,” Media, Culture & Society 39, no. 7 (2017): 1027–1042, https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716686672, 1030.

[51] “The Propaganda of the Putin Era,” Institute of Modern Russia, 13 de noviembre de 2012.

[52] Van Herpen, Putin’s Propaganda Machine, 110.

[53] Erin Baggott Carter and Brett L. Carter, “Questioning More: RT, Outward-Facing Propaganda, and the Post-West World Order,” Security Studies 30, no. 1 (2021): 49–78, https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2021.1885730.

[54] Larissa Doroshenko and Josephine Lukito, “Trollfare: Russia’s Disinformation Campaign During Military Conflict in Ukraine,” International Journal of Communication 15 (2021): 4662–4689, https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/16895/3587, 4683.

[55] Paul and Matthews, “Firehose of Falsehood”, 2.

[56] Mejis and Vokuev, “Disinformation and the media”, 1034.

[57] Margarita Jaitner and Peter A. Mattsson, “Russian Information Warfare of 2014,” in 7th International Conference on Cyber Conflict: Architectures in Cyberspace, eds. M. Maybaum, A.-M. Osula, and L. Lindström (Tallinn: NATO CCD COE Publications, 2015), 9.

[58] Joshua P. Mulford, “Non-State Actors in the Russo-Ukrainian War,” Connections QJ 15, no. 2 (2016): 89–107, https://doi.org/10.11610/Connections.15.2.07, 93.

[59] Van Herpen, Putin’s Propaganda Machine, 198–199.

[60] Mulford, “Non-State Actors,” 96.

[61] Elie Saikali, “Patriarch Kirill: The politically influential head of the Russian Orthodox Church,” France 24, 9 de enero de 2023, https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20230109-patriarch-kirill-the-politically-influential-head-of-the-russian-orthodox-church.

[62] Paul and Matthews, “Firehose of Falsehood”, 1.

[63] Paul and Matthews, “Firehose of Falsehood”, 2–4.

[64] Paul y Matthews, “Firehose of Falsehood”, 6.

[65] Leon Aron, “Russian Propaganda: Ways and Means” (American Enterprise Institute, 2015), http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep03227, 5.

[66] Treyger, Cheravitch, and Cohen, Russian Disinformation Efforts, 69.

[67] Treyger, Cheravitch, and Cohen, Russian Disinformation Efforts, 70.

[68] Treyger, Cheravitch, and Cohen, Russian Disinformation Efforts, 71.

[69] Treyger, Cheravitch, and Cohen, Russian Disinformation Efforts, 72.

[70] KJ Boyte, “An Analysis of the Social-Media Technology, Tactics, and Narratives Used to Control Perception in the Propaganda War Over Ukraine,” Journal of Information Warfare 16, no. 1 (2017): 88–111. ISSN 1445-3347, 98.